What Is Net Core?

Guest: Jamie Taylor19 Jul 2017 | 0 Comments

This is a dive into .NET Core, with a focus on what a beginner can expect of the open source framework that could, and how to get started with it.19 Jul 2017 | 0 Comments

This is a dive into .NET Core, with a focus on what a beginner can expect of the open source framework that could, and how to get started with it.This blog post is about .NET Core, with a focus on what a beginner can expect of the open source framework that could, and how to get started with it.

It has been authered by Jamie Taylor of A Journey in .NET Core, he was a guest on the show where he came and spoke about .Net Core, you can listen to his episode here.

.NET Core is a cross platform, open source re-implementation of the .NET Framework. It is actively maintained by Microsoft and a huge community of developers over on GitHub.

Lets just dissect that for a moment:

That’s right, Microsoft have embraced open source. Back in 2016, Microsoft bought Xamarin and began integrating it into the Microsoft developer tool set. Off of the back of that, the dnx teams decided to push what were the earliest versions of (what became) .NET Core to the public. The dnx work was based on the work which went into Roslyn, and formed the basis for both .NET Core and ASP.NET Core (both are separate teams, but some work bleeds over).

The initial version of the .NET Framework was released in 2002, alongside Visual Studio.NET, which was the latest version of Microsoft’s Visual Studio IDE. The .NET Framework has a long history of development, going back to it’s initial announcement as NGWS (Next Generation Web Services) back in 1997.

Microsoft’s end goal is not to replace .NET Framework with .NET Core, but to add it to the .NET eco-system as an alternative for developers who need to build cross platform applications.

Lets say that you are a Linux (or even MacOS) based developer and you want to try out this C# and .NET business but don’t have a Windows licence.

Let’s say that you’re looking to write a micro service, but don’t want to use Node.js or any of the other JavaScript-on-the-server frameworks.

Let’s say that you want to take a pre-existing MVC application written in .NET Framework and run it on a Linux box (for cheaper hosting).

Let’s say that you want the “write once, build anywhere” that Java promised, but with C#.

You can achieve all of those things with .NET Core.

.NET Core supports Console Applications, Web Applications (asp.net MVC, WebApi), Class Libraries and Unit Tests.

This doesn’t sound like a lot, but it covers most of the application types that you might want to build. You can even build cross platform 3D video games with it, which is pretty neat.

It doesn’t support creation of WinForms or UWP applications. There are builds of GTK and other open source Form-like libraries which support .NET Core.

However, UWP can use any libraries that are built with .NET Core as long as they explicitly target version 1.6 or above of the .NET Standard.

This is a bit of sticky subject at first, but it’s really quite simple.

.NET Standard is a standard. It’s that simple.

It lists which APIs you can expect a version of a given framework within the .NET eco-system to support. I’ve written about .NET Standard over on A Journey in .NET Core. It’s a pretty big article which goes into the whats, whys, and wheres.

The tl;dr version is that as each framework in the .NET eco-system (.NET Framework, .NET Compact Famework, Mono/Xamarin) evolved, they all had their own versions of the BCL (Base Class Library). Eventually these different frameworks started to differ in what features where available in their BCLs.

Something written for Xamarin wouldn’t necessarily work with a .NET Framework library because the .NET Framework library might have exposed apis in it’s BCL which Xamarin couldn’t use (or vice versa).

Then along game Immo Landwerth and he fixed it all… sort of.

He and his team started drafting a document which described all of the apis that you could expect something within the .NET eco-system to have. He’s actually put out a series of really good Youtube videos explaining the whole thing, and they’re well worth watching.

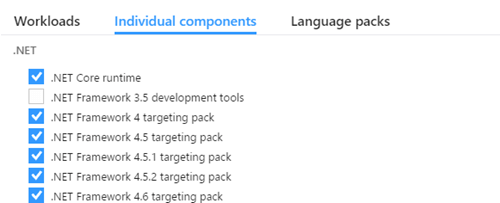

The first thing you’ll need is the SDK. You’ll only need to go and get this if you’re not running Visual Studio 2017 Update 2 (which is only available for Windows 10), as it’s one of the installation options. It’s available for Windows, MacOS, and most distributions of Linux.

Heading over to https://dot.net/core is the first thing that you’ll want to do. The site should detect your operating system and give you a page with information on how to install it for your setup.

Once you’ve got the SDK downloaded and installed, you can head over to the terminal (I tend not to call it the command prompt) and issue the following command:

> dotnet --version

you should get something along the lines of:

1.0.4

as a response (don’t worry if the version number is different, it’s just an example). This means that you’ve successfully installed the .NET Core SDK.

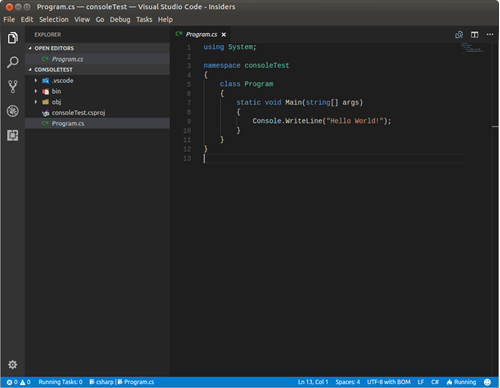

The next thing you’ll need is an editor. I’m one of those strange .NET developers who doesn’t run Windows at home (I run an Ubuntu PC and a have a Mac laptop), so I use Visual Studio Code as my editor/IDE. It’s extremely lightweight, fast, and open source. Oh, and it’s made my Microsoft.

If you go down the VS Code route, I’d recommend installing the OmniSharp extension to get full C# support.

Now that you have an editor and the SDK, we need to build something. Head back to the terminal and issue the following command:

> dotnet new console --name consoleTest

This will create a directory called consoleTest and a set of subdirectories within it with the code for a basic console application.

Within the consoleTest directory you’ll find two files:

The csproj contains all of the information that MSBuild (more on that in a moment) needs to know in order to build the application. Let’s take a quick look at it:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk"><PropertyGroup> <OutputType>Exe</OutputType> <TargetFramework>netcoreapp1.1</TargetFramework> </PropertyGroup>

</Project>

This is one of the simplest csproj’s you’ll ever see as a .NET Core developer. The first thing it does is tell MSBuild to use the .NET Sdk to build the application.

Two things:

This means that it brings together all sorts of tools which will be used to build the app. Things like Roslyn (the C# compiler), command line tools, NuGet package manager; all of that great stuff. It then uses all of these tools to process your source code and build a set of binaries.

This one is a little weird, right? We’re building a .NET Core app, so why are we using the .NET Sdk?

Well, taking a look at the source for Microsoft.NET.Sdk (I did say that .NET Core was entirely open source, right?), we can see that it’s part of the dotnet sdk repository, which provides:

Core functionality needed to create .NET Core projects, that is shared between Visual Studio and CLI

In fact, this is a NuGet package and needs to be restored before we can build the application (more on that in a second).

Next is this section:

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp1.1</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

Here we’re telling MSBuild to make an executable binary file, and that it should use netcoreapp1.1 as it’s framework.

This is where the confusion sets in again. netcoreapp1.1 is a framework; but .NET Core is a framework too, right? I’ll let Microsoft clear this up for us:

The terms framework and platform are sometimes confusing given how they’re used in phrases and their context. For example, you’ll see .NET Core described as a framework in the context of building apps and libraries and also described as a platform in the context of where app and library code is executed. A computing platform describes where and how an application is run. Since .NET Core executes code with the .NET Core Common Language Runtime (CoreCLR), it’s also a platform. The same is true of the .NET Framework, which has the Common Language Runtime (CLR) to execute app and library code that was developed with the .NET Framework’s framework objects, methods, and tools.

The objects and methods of frameworks are called Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). Framework APIs are used in Visual Studio, Visual Studio for Mac, Visual Studio Code, and other Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) and editors to provide you with the correct set of objects and methods for development. Frameworks are also used by NuGet for the production and consumption of NuGet packages to ensure that you produce and use appropriate packages for the frameworks that you target in your app or library.

When you target a framework or target several of them, you’ve decided which sets of APIs and which versions of those APIs you’d like to use. Frameworks are referenced in several ways: by product name, by long or short-form framework names, and by family.

(the above was taken from The page describing the term frameworks at Microsoft’s .NET Core documentation)

netcoreapp1.1 is also related to .NET Standard version 1.6 (which can be seen at the above linked page). This means that we have access to all of the APIs which .NET Standard 1.6 guarantees will be available, regardless of the host operating system which our application will run on.

(Again, I’d recommend taking a look at my post on .NET Standard for a much more in depth description)

This is where all of our code lives. If you’re familiar with C# (or even with other C-based languages, including Java) then this should be pretty easy to read.

using System;namespace consoleTest { class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine(“Hello World!”); } } }

If you’re not familiar with C#’s syntax, then there are a tonne of resources out there for learning C#. I’d recommend “C# fundamentals for absolute beginners” as it’s on Microsoft’s Virtual Academy, and it’s free.

I’ve already mentioned that we need to restore packages.

Microsoft have taken the idea of Ruby gems and expanded it - to be fair, they’re not the only folks to have done this - and created a service called NuGet (which is pronounced “New Get”). NuGet hosts packages of code (usually libraries) which your application can consume, in order to make developing your app faster. If Ruby isn’t your thing, then you must have heard of npm right? NuGet is a little like npm (but without any of that left-pad nonsense).

In order to build our .NET Core application, we need to restore any NuGet packages that we rely on. We currently rely on the System package, do let’s restore that:

> dotnet restore

This will spawn a process which will look through the source code for our application and download all of the packages necessary for building the application. Which, it turns out, is quite a lot. To see just how many packages we need to restore, delete the obj directory that .NET Core creates for us (it will be in the same directory as the source code) and attempt to build the application:

> dotnet build

You’ll get a handful of wonderful red error messages along the lines of:

error CS0400: The type or namespace name 'System' could not be found in the global namespace (are you missing an assembly reference?)

So we’d better re-restore our packages and carry on.

As a side note about packages: the contents of the packages are downloaded to a special directory on your machine called .nuget/packages. This directory is found in your user profile area (~ on Unix like machines, and C:\users\user.name on Windows)

Once we’ve restored the packages for our application, we can build and run it. In .NET Core 1.x these were two separate actions, aka:

> dotenet build > dotnet run

But in .NET Core 2.x, the same can be achieved by running:

> dotnet run

Doing this should produce terminal output similar to this:

> dotnet build Microsoft (R) Build Engine version 15.1.1012.6693 Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.consoleTest -> /Code/consoleTest/bin/Debug/netcoreapp1.1/consoleTest.dll

Build succeeded. 0 Warning(s) 0 Error(s)

Time Elapsed 00:00:02.16

Our application just built successfully. Let’s try running it:

> dotnet run Hello World!

We can take the consoleTest.dll file and run it ANYWHERE which has .NET Core installed, including Linux distributions or MacOS.

To do that, we just bring up the terminal wherever we paste the DLL and issue the:

> dotnet run

command, and .NET Core will load and run the application for us. Even if it was built on Linux but run on Windows.

That’s pretty impressive.

Of course not. Depending on which operating system you’re running, there are a number of options available to you.

| Operating System | Visual Studio Code | Visual Studio | Visual Studio for Mac | Rider |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windows | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Mac OS Sierra | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ubuntu Linux (.deb) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Red Hat (.rpm) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Please leave a comment, positive, negative or just something weird.

Jamie is a .NET contractor, podcast host, gamer, bass player, and productivity novice.

He loves to talk .NET Core (as evidenced by his past appearances on the show), and is still on a quest to take all ten of the top ten spots in the apple podcast ratings - even if it means creating thousands of podcasts in the process.